by Alessandro De Giorgi*

The materials presented in this blog series draw from an ethnographic study on prisoner reentry I have been conducting between March 2011 and March 2014 in a neighborhood of West Oakland, California, plagued by chronically high levels of poverty, unemployment, homelessness, drug addiction, and street crime. In 2011, with the agreement of a local community health clinic that provides free basic health care and other basic services to marginalized populations in the area, I have been conducting participant observation among several returning prisoners, mostly African American and Latino men between the ages of 25 and 50. In this series of blog entries, I will be presenting ethnographic snapshots of some of these men (and often their partners) as they struggle for survival after prison in a postindustrial ghetto. For more detailed information on this project, please read here. Other episodes in this series:

#1 – Get a Job, Any Job

#3 – Home, Sweet Home

#4 – In the Shadow of the Jailhouse

• • •

—It’s important to get a job. Later, you may decide to try for a better job.

[Parolee Information Handbook, California Department

of Corrections & Rehabilitation]

During the heyday of industrial capitalism, when relatively stable labor markets, higher wages, and a minimum of social protections made work discipline a viable path to social citizenship, wage labor constituted a plausible avenue for reintegrating former prisoners (Simon 1993, 39–67). In contemporary deregulated capitalism, characterized by highly segmented labor markets and soaring levels of economic insecurity, this is no longer the case for the burgeoning populations of mostly African American and Latino men who every day are ejected by the US penal machine and dumped back into the segregated urban neighborhoods they came from. In the postindustrial ghetto, ex-convicts scramble to fill the ranks of the working poor, caught in a loose network of post-carceral control largely delegated to private actors—halfway houses, drug rehabilitation centers, reentry programs, and especially low-wage employers eager to hire the most vulnerable workers (Miller 2014). Relegated to a status of liminal incorporation, to borrow Orlando Patterson’s powerful analysis of slavery and social death (Patterson 1985, 45), the few who find employment experience the untamed violence of degraded work (Doussard 2013) under neoliberal capitalism—one paycheck away from homelessness, abject poverty, and starvation.

• • •

Ray is a 49-year-old African American who was released from prison in 2010, after serving eleven years. This was his “second strike,” following a two-year prison sentence served in the late 1980s. As a child, Ray was raised by his single mother in the infamous Nickerson Gardens projects in Watts, Los Angeles. Although he likes to reminisce about his days as a gangster in the streets of LA, before ending up in prison Ray experienced several stints of working-class life. In the 1990s, he had a temporary job unloading trucks at a warehouse; he worked for five years at a Taco Bell restaurant and then for another three years at Home Depot. Ray is proud of his working past, which he sees as a gateway to a successful future after prison. Indeed, after his release he didn’t waste any time. He immediately signed up as a volunteer at a community health clinic in West Oakland and eventually was hired as a part-time employee. He worked there for a few months at $12 an hour ($960 per month), but he was only on call for a few hours a week and was soon dismissed for lack of funds. The pastor who runs the clinic helped him land another part-time job at a furniture shop, where he worked for five months at $10 an hour ($800 per month). This job was also short-lived, however, since Ray was fired when the store went out of business. For the next three months his only source of income was $200 a month from General Assistance (which he must repay since the county considers it “a loan to the individual receiving aid”). In the summer of 2012, he reconnected with an old friend and colleague from Taco Bell from 1992 who was now a manager in an East Oakland KFC restaurant. He hired Ray as an on-call employee, at $8.00 an hour. Ray has kept this job, at the same salary, ever since.

Ray is a 49-year-old African American who was released from prison in 2010, after serving eleven years. This was his “second strike,” following a two-year prison sentence served in the late 1980s. As a child, Ray was raised by his single mother in the infamous Nickerson Gardens projects in Watts, Los Angeles. Although he likes to reminisce about his days as a gangster in the streets of LA, before ending up in prison Ray experienced several stints of working-class life. In the 1990s, he had a temporary job unloading trucks at a warehouse; he worked for five years at a Taco Bell restaurant and then for another three years at Home Depot. Ray is proud of his working past, which he sees as a gateway to a successful future after prison. Indeed, after his release he didn’t waste any time. He immediately signed up as a volunteer at a community health clinic in West Oakland and eventually was hired as a part-time employee. He worked there for a few months at $12 an hour ($960 per month), but he was only on call for a few hours a week and was soon dismissed for lack of funds. The pastor who runs the clinic helped him land another part-time job at a furniture shop, where he worked for five months at $10 an hour ($800 per month). This job was also short-lived, however, since Ray was fired when the store went out of business. For the next three months his only source of income was $200 a month from General Assistance (which he must repay since the county considers it “a loan to the individual receiving aid”). In the summer of 2012, he reconnected with an old friend and colleague from Taco Bell from 1992 who was now a manager in an East Oakland KFC restaurant. He hired Ray as an on-call employee, at $8.00 an hour. Ray has kept this job, at the same salary, ever since.

By the narrow standards of prisoner “reentry,” Ray’s is a success story: he managed to stay out of prison, except for a few days in jail following a fight with his partner Melisha; he has been employed for most of the three years since his release; and his use of alcohol has not compromised his parole. In the following notes, however, I try to complicate this picture by providing two snapshots of Ray’s life as a member of the working poor in the post-prison labor market.

August 15, 2012

At 9 am I receive a message from Melisha’s cellphone:

Ray told me to send this pix of him and to ask u if u can bring him a Four Loko [malt liquor] for him so it can be here for him when he get off work and a frew dollar for me to play my ticket and he also said much luv to u homie for everything because if it wasn’t for u he wouldn’t have his old job back that what he just told me to text to u smile.

Two pictures of Ray wearing his red KFC uniform supplement the text message. His right arm is on his chest, with his hand forming the bent three-finger West Coast sign.

I decide to visit Ray to wish him good luck for his first day of work at KFC. When I walk inside their apartment, they both seem very excited. Melisha is applying makeup using the stained mirror in the bathroom, while Ray is sitting comfortably on a couch in his red KFC uniform, with a large smile on his face. For a moment I think that they look like a couple getting ready to go on a vacation. I sit on the sofa and ask Ray how he feels about his new job:

Alex: So, is it full time?

Ray: No. I’m on call.

Alex: What about pay?

Ray: We haven’t discussed that yet because as a manager I’ll do salary not wages. So I start tonight, right now, on wages.

Alex: How much?

Ray: Like probably 12 dollars, something like that. I get a salary plus bonuses.

Alex: What about healthcare, do you get it?

Ray: Everything.

Alex: As soon as they hire you, you get it?

Ray: No, no, no, no. Once I start my manager position, then I get full … full everything, full everything.

Alex: So you’re happy?

Ray: Yeah! And I’ll probably move out of here … [he lights up a miniscule smoked-down joint and inhales it with a hissing sound]

Alex: Where do you want to go?

Ray: Somewhere by the lake [Lake Merritt, Oakland]. Back in the day I used to live in Alameda. Had a nice place right by the beach in Alameda … swimming pool, Jacuzzi. Hell yeah!

Alex: Did you rent or was it yours?

Ray: I rented. Probably … about another five years … If I be here another five years, like I was before, I could probably lean down on a home.

Before leaving, I walk to the fridge to leave the two cans of malt liquor I had brought. The fridge is empty, except for a bottle of Pepsi, a half-eaten hotdog, and a bag of McDonald’s fries. I look at Ray, who is still struggling with his joint, and he assures me that he won’t drink the liquor before work but only after he comes back from KFC, later tonight, “to celebrate the new life.”

January 14, 2013

Five months have passed since Ray started working at KFC. He calls me this morning: “Bro, can you bring us something to eat today? We starving…”

Two weeks ago they received an eviction notice from their small ground-floor apartment in East Oakland, which they must leave by Sunday. Back in December, Ray and Melisha were arrested after getting involved in a late-night fight outside the apartment, which prompted a neighbor to call the police. The police took them to jail, where they spent the next three weeks. Partly as a consequence of this, they have not been able to keep up with their monthly rent of $900, so they now owe $600 to the landlord. Over the last few days they have been moving their few appliances out of the apartment. During my last visit, they squeezed their belongings into a few garbage bags, which I helped them take to a cheap self-storage service in East Oakland. All that is left in the apartment is the mattress they plan to sleep on until the sheriff kicks them out, and the old laptop I lent to Melisha so that she could apply for jobs online.

When I pull in front of their apartment, they are sitting on the sidewalk. Sleepy, the small pinscher Ray adopted soon after being released from prison in 2011, starts jumping around when he sees me. “How are you guys doing?” I ask. Melisha barely acknowledges my presence and keeps staring at her phone—a clear sign that she and Ray must have been arguing. Ray replies with his usual sarcasm: “Exactly as planned, bro! We are homeless and starving!” I give Melisha the two bags of groceries I brought for them, and she steps inside the apartment.

Ray asks me to follow him into their car, because “we need to have a man-to-man conversation.” We sit in the Camaro, which is slowly falling apart. It is even messier than usual, with dirty clothes, empty KFC bags, and other stuff scattered about. I wonder once again how they could have paid $4,000 to a shady East Oakland dealer for a car in such abysmal condition: the stained upholstery is peeling off, the seats are dotted with cigarette burns, the wires are coming out from under the steering wheel, and the window on the driver’s side doesn’t work anymore. They paid $2,000 up front, thanks to a tax return Ray had finally received after months of anticipation, and agreed to pay the rest in twelve installments of $250 each—though of course they would never keep up with the payments.

Ray tells me they are desperate for money. He has only been able to work for a few hours a week at KFC since being released from jail last month. He still works on call for $8.00 an hour and makes less than $200 each week. Meanwhile, Melisha has been unable to find any job—despite filling out applications at McDonald’s, Pack n’Save, Ghirardelli, and several other places—and her SSI payments were suspended while she was in jail.

Alex: Right now … The two of you, how much cash do you have?

Ray: Nothin’.

Alex: Nothing?

Ray: Zero. Pennies. Oh, here you go [searches into his pockets, then opens his hand to show me a few dimes]. That’s our savings right here. Oh yeah … And our free cookie [hands me a greasy paper bag from KFC with a half-melted chocolate chip cookie inside].

Alex: A free cookie?

Ray: Yeah! Free cookie, from KFC. Free cookie, that’s all we got right here.

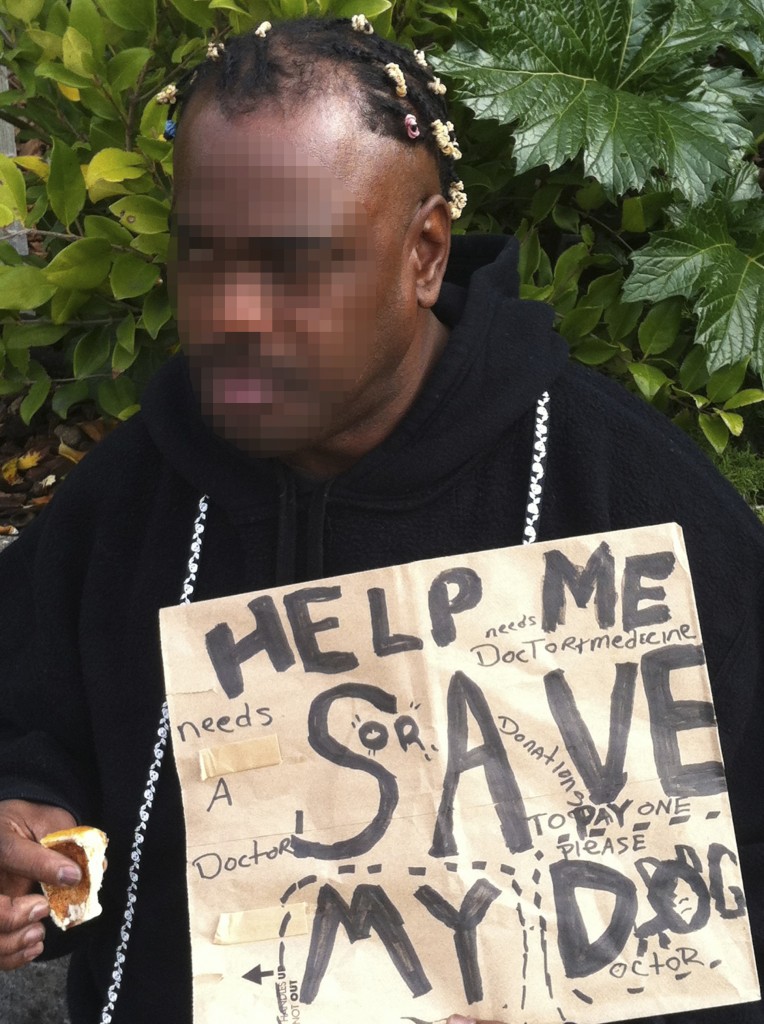

They must leave the apartment by the end of the week and need to find a new place to stay. Ray tells me that one option would be a trailer park right underneath the freeway’s ramp around the corner. While we’re talking in his car, Ray takes out a piece of cardboard on which he has written, with a black marker: “HELP ME SAVE MY DOG … needs a Doctor! Donations to pay one please.” He explains that today he plans to panhandle, with the dog by his side, at the entrance of a Safeway supermarket located in a nearby residential area. He tells me that he is optimistic about how much money he will make, because Sleepy attracts “middle-class women” who have pity for him.

They must leave the apartment by the end of the week and need to find a new place to stay. Ray tells me that one option would be a trailer park right underneath the freeway’s ramp around the corner. While we’re talking in his car, Ray takes out a piece of cardboard on which he has written, with a black marker: “HELP ME SAVE MY DOG … needs a Doctor! Donations to pay one please.” He explains that today he plans to panhandle, with the dog by his side, at the entrance of a Safeway supermarket located in a nearby residential area. He tells me that he is optimistic about how much money he will make, because Sleepy attracts “middle-class women” who have pity for him.

During this conversation, Melisha comes out of the apartment and tells me that they need to go to the storage place to retrieve the small microwave she uses to warm up the fried chicken leftovers Ray brings home from KFC on the days he works. We drive there and I see their stored items: a few plastic bags with clothes and shoes, a pair of speakers we collected from the trash a few months ago, some old, valueless furniture, a broken computer screen, also from the trash, and some cheap Halloween decorations. Upon opening my car trunk to load the microwave, Ray sees my Trader Joe’s grocery bags and says, “This here is how I should be eating … for my high pressure, diabetes, and shit … not that fuckin’ KFC chicken.”

Back at their apartment we drop off the microwave and decide to drive to the trailer park to investigate and inquire about the rent. Ray drives the Camaro while Melisha and I follow him in my car. She cries most of the time, complaining about the situation. She repeats, “I never been homeless before. I always had my own place.” When we arrive, I see the run-down mobile home where they are hoping to move. The trailer park looks a lot like a homeless encampment. Ray asks me to talk to the manager, hoping that my middle-class credentials will spare them the cost of a credit report. But his hopes are frustrated: a rather rude white man in his 60s tells me that to move in Ray and Melisha need to pay $1,000 upfront—first month, deposit, and credit report. We tell him that we need to think it over and leave.

We drive toward the Safeway where Ray plans to panhandle, but Melisha makes it clear that she doesn’t want to be there with him and will wait in the car. She has been crying along the way and says that Ray had lied to me about not having a drink since his release from jail. He’s been drinking a lot, she says. She is depressed about this and everything else that’s going on in their lives.

At Safeway, Ray gets his sign and dog ready, and sits by the side of the supermarket’s entrance. He seems in good spirits, and we crack a few jokes about what he’s doing; he doesn’t feel ashamed. I stay at a distance because Ray says that if passersby see me they will think it’s a joke and won’t give him any money. So I sit on a wall nearby and watch the scene. The few people who stop by—mostly elderly white women on their way to the supermarket—are clearly attracted by the little dog, while barely acknowledging Ray and mostly ignoring his solicitation for money. Meanwhile, Melisha is sitting in the front seat of the Camaro, playing with her phone and pretending that she doesn’t know Ray. Around 4 pm, almost four hours into the panhandling session, Ray has made $20 and a few pennies. He sets aside $10 for gasoline, and gives $5 to Melisha (who immediately buys a lottery ticket). He spends the rest on a few cans of malt liquor from the liquor store around the corner.

At the time of this writing, almost four years after his release, Ray is still working on call at KFC for $8.00 an hour, while Melisha is still unemployed. Ray only panhandled a few more times after that day at the Safeway, because he says it’s not worth the money. I still buy them extra groceries fairly regularly.

References

Doussard, M. 2013. Degraded Work: The Struggle at the Bottom of the Labor Market. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Simon, J. 1993. Poor Discipline: Parole and the Social Control of the Underclass, 1890-1990. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Miller, R. 2014. “Devolving the carceral state: Race, prisoner reentry, and the micro-politics of urban poverty management.” Punishment & Society 16(3): 305-335.

Patterson, O. 1985. Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

* Alessandro De Giorgi is Associate Professor and Graduate Coordinator at the Department of Justice Studies, San José State University, and a member of the Social Justice Editorial Board. He thanks his research assistants Carla Schultz, Eric Griffin, Hilary Jackl, Maria Martinez, Samantha Sinwald, Sarah Matthews, and Sarah Rae-Kerr for their invaluable contribution. For a more detailed description of the project, see here.

• • •

Alessandro De Giorgi, “Reentry to Nothing #2—The Working Poor.” Social Justice blog, 10/17/2014. © Social Justice 2014.